OUT OF

THE BOX

Studio Photographs from the Harald Mante Collection

OUT OF

THE BOX

Studio Photographs from the Harald Mante Collection

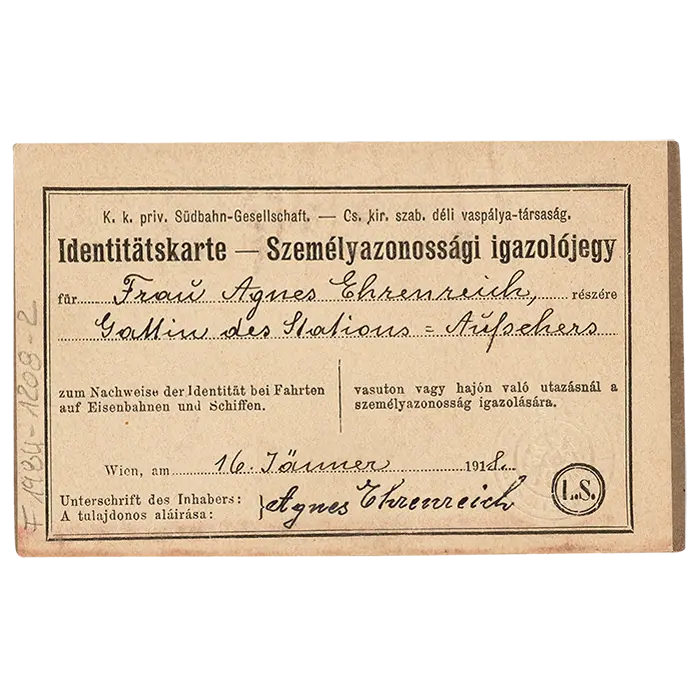

In 2022 the Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte cast a fresh eye over one part of its photographic collection. This review has yielded insights, for the first time, into a body of photographs acquired in the mid-1980s from the photographer and collector Harald Mante.

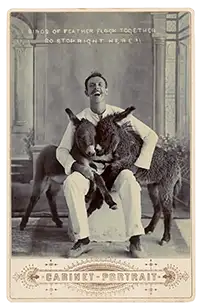

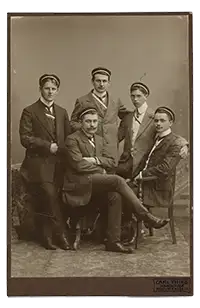

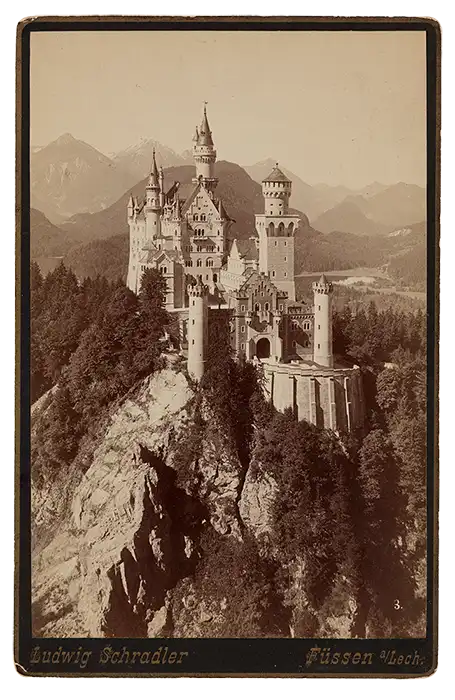

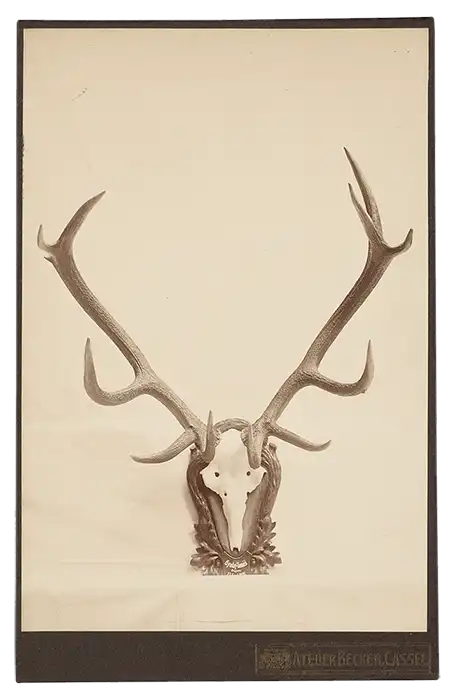

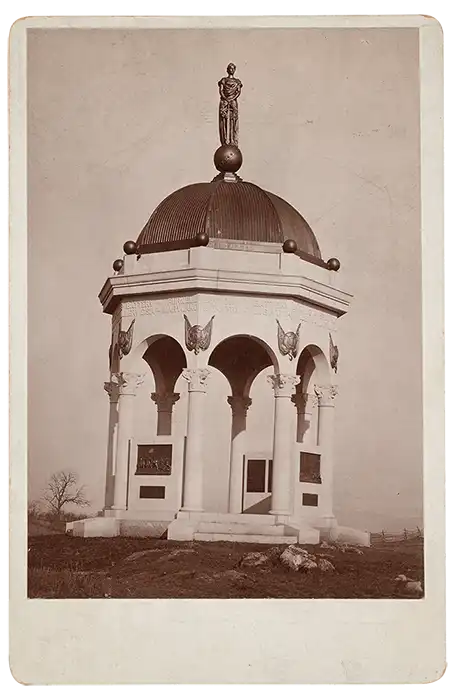

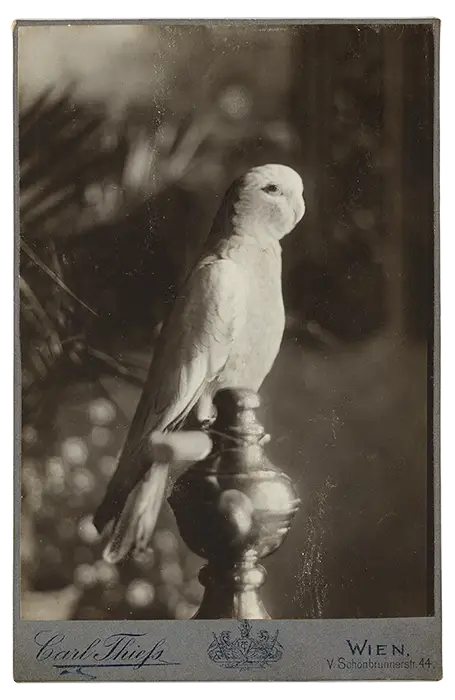

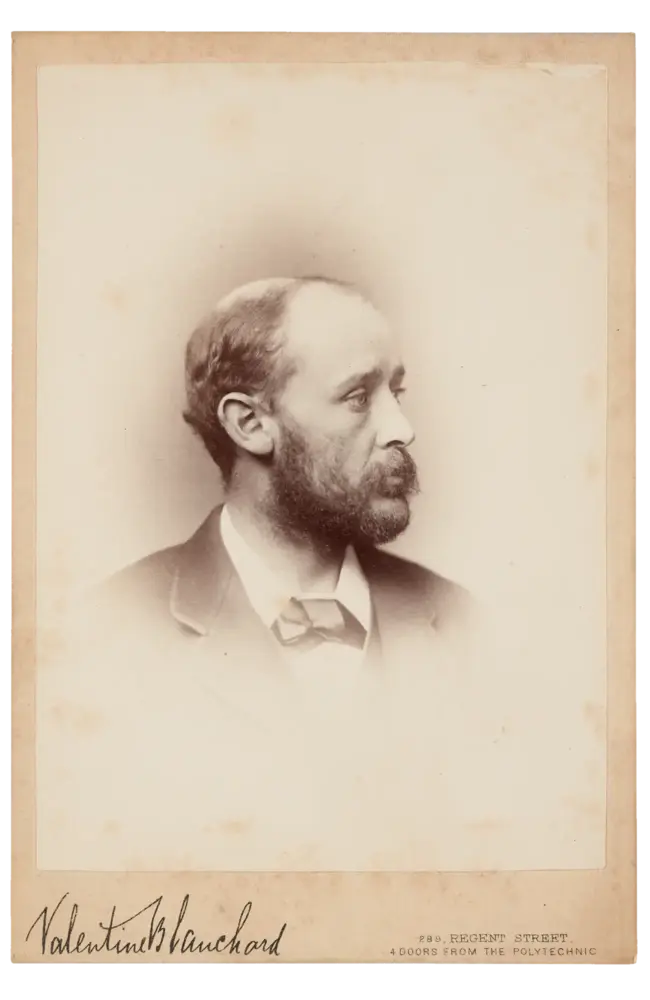

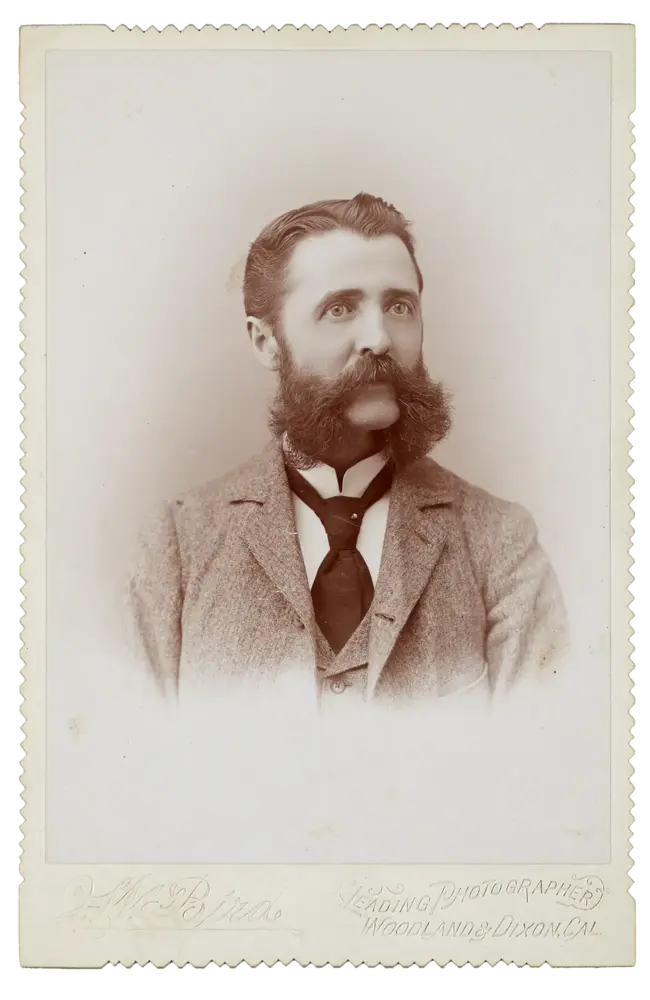

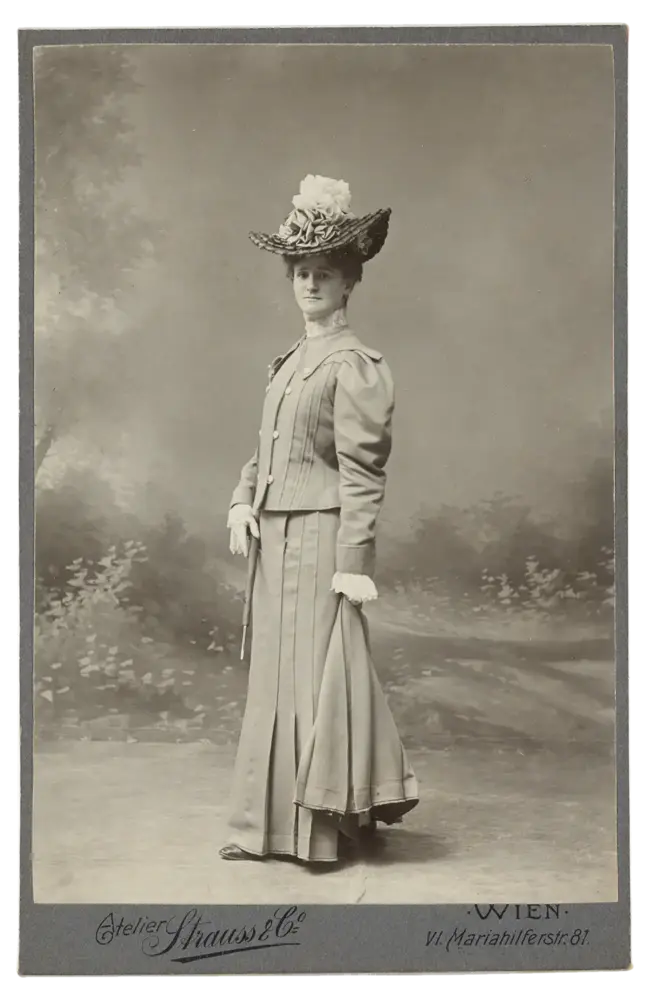

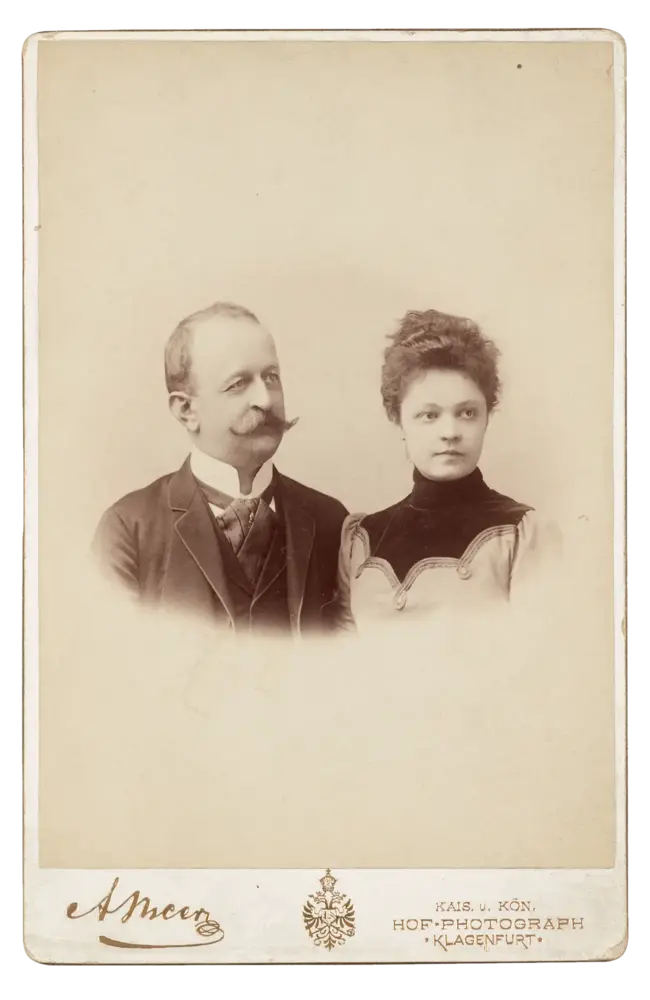

Out of the Box. Studio Photographs from the Harald Mante Collection is devoted to an almost forgotten photographic phenomenon: the cabinet card – a standardised pictorial format that was especially popular in portrait photography in the second half of the 19th century. In this online exhibition, we invite you to take a deep dive into this multifaceted visual medium, its language of form and the ways it uses images. Cabinet cards offer an insight into the zeitgeist of portrait photography in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Studio Photographs from the Harald Mante Collection

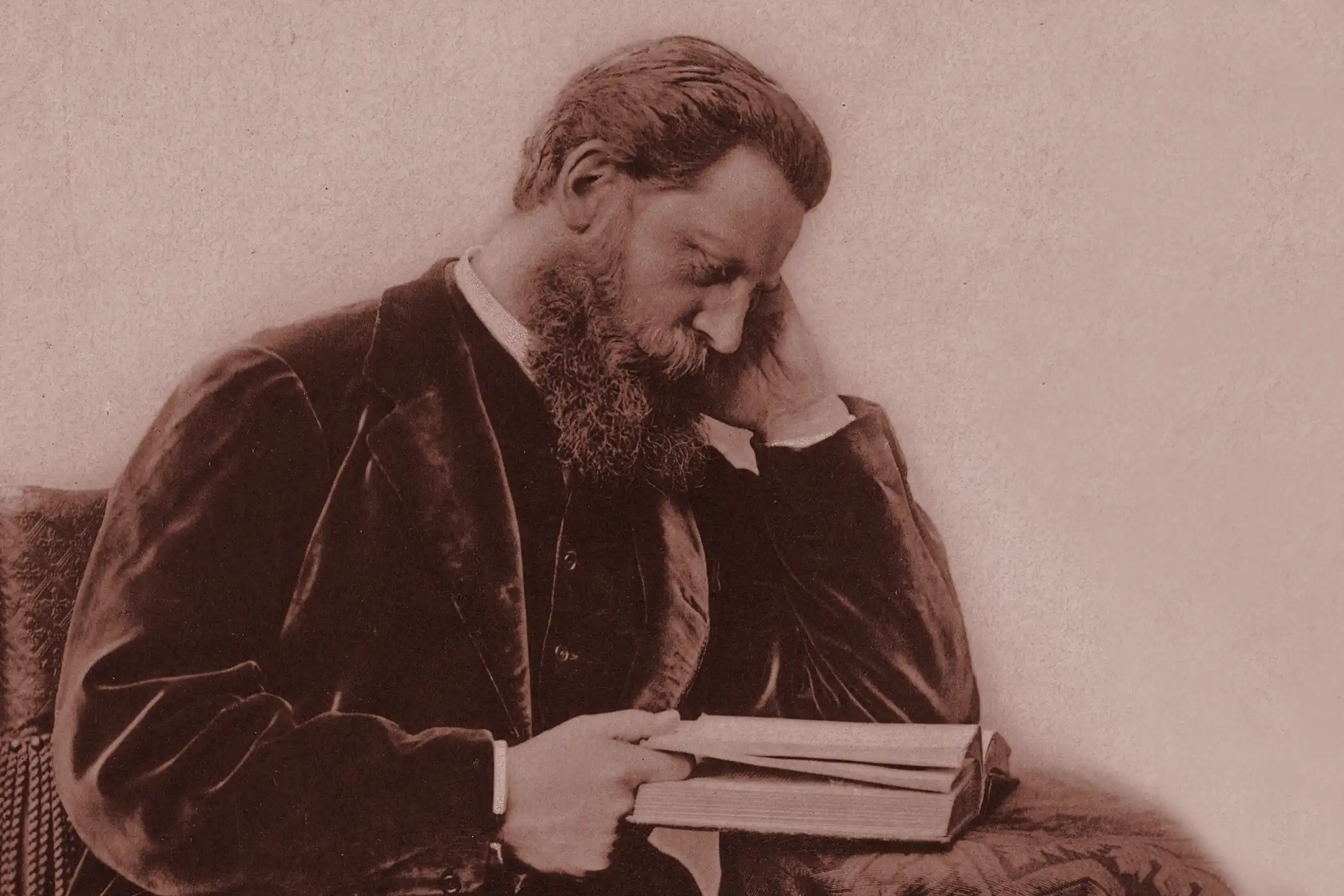

Harald Mante’s photographic collection comprises over 10,000 photographic objects from the first 100 years of the history of photography. The collection reflects photographer Harald Mante’s interest in applied photography and in the material modes of presentation of the photographic image.

The Harald Mante Collection contains some 2,500 cabinet cards – predominantly historical portrait photographs. The cards come from 40 different countries and from every continent. Carrying pictures of people, buildings, animals, objects and landscapes, they illustrate a large part of the photographic spectrum of their epoch. The focus, however, lies on portraiture.

1

The photographic portrait

in the 19th century

Creating a photographic portrait has become an integral part of today’s image culture and has never been easier. We can visualise our physical presence in the world simply by pressing the button on a camera or a smartphone screen. But that was not always the case.

Standardised image sizes, a handy format, reasonably priced photographs: these pictures spread worldwide.

Portrait of a woman, Auty Ltd, Tynemouth, England, c. 1880, cabinet card © Jürgen Spiler

What is a

cabinet card?

A cabinet card is a photograph mounted onto a card and was particularly popular in the field of early portrait photography. It has a standard format of ca. 4 ½ × 2 ½ inches (ca. 16.5 × 11.5 cm). From 1866 until around 1920, the cabinet card was a staple product of photographers’ studios. Other such photo cards included the cabinet card’s famous forerunner, the carte-de-visite .

-

- Date: ca. 1860—1920

- Size: ca. 16,5 × 11,5 cm / 4 ½ × 2 ½ in.

- Materials: Paper, card

- Technique: Albumen print on paper, mounted on card

Excursus: Photographic materials & techniques

-

In the 19th century, albumen was a widely-used process for making photographic prints. It was invented in 1850 by Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard. In an albumen print, the image is suspended in a layer above the paper, rather than being embedded in the paper fibres. The paper is first coated with albumen (egg white) and thereby given its glossy surface. It is next sensitised to light with a silver nitrate solution, before then being exposed together with the photographic negative (usually collodion on glass). Albumen prints are characterised by their richness of detail. Albumen supplanted direct-positive processes such as the daguerreotype+, since it allowed countless prints to be made from a negative plate.

-

The daguerreotype was the first photographic process in the 19th century to be used commercially. In this method, the photographic image is fixed on a mirror-polished metal plate. The daguerreotype was distinguished by the fact that, right from the start, it delivered nuanced and finely structured images, which maintain their definition even under a magnifying glass.

Exposure time:

Up to 1840: 15—30 minutes

As from 1840: 25—90 seconds

As from 1842: 10—60 seconds -

Collodion is a viscous solution of nitrocellulose in a mixture of alcohol and ether. In the photographic industry, it is used with a solution of silver nitrate to make photographic plates light-sensitive. Due to its adhesive properties, collodion is also used in medicine to close small wounds.

Prior to the advent of photography, having your portrait made was something only possible for privileged social classes who could afford a painter. In the early years of photography, sitting for one of its new, true-to-life portraits was likewise still expensive.

Photography as mass-produced item

The history of photography is characterised by numerous phases, distinguished by technical developments and different processing and printing methods. In the mid-19th century, various new processes were invented. Changing photographic practices also influenced the content of photographs and how they were used.

Queen Viktoria, André Adolphe-Eugène Disderi, Carte-de-visite, um 1866 © Jürgen Spiler

Technical advances from the 1850s onwards, such as the wet collodion process and cameras equipped with multiple lenses, made it possible to print several positive images from a single glass negative. This made photography both faster and cheaper. Even its quality now surpassed that of the daguerreotype , formerly so popular and prized for its uniqueness. .

Start of a new era: the photographic print

Thanks to technical advances, photographs became faster and cheaper to produce. André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri seized upon this. He wanted to find a way of making photography more affordable and accessible to a broad clientele. Around 1851 he invented the carte-de-visite , a standardised print format that revolutionised photography. This was the beginning of “cardomania” .

“Disdéri started a craze that […] gripped the whole world, […] because he gave us much more for much less.”

Nadar (French photographer, caricaturist and writer), ca. 1900

The small, inexpensive calling card bearing a photographic portrait became all the rage and contributed significantly to the spread of photography as a mass product. An entire photo-card industry sprang up, enabling people to have a portrait of themselves made at an affordable price. In no time, the market was positively flooded with thousands of cheap portraits.

Alongside the cabinet card, other standardised but less common sizes, such as the Victoria, promenade, boudoir and imperial formats, developed out of the carte-de-visite. These pictures were produced and printed by the thousands.

ca. 1858

63 × 102 mm

ca. 1870

83 × 122 mm

ca. 1866

105 × 165 mm

ca. 1875

108 × 210 mm

ca. 1875

134 × 215 mm

ca. 1875

175 × 250 mm

Around 1866, the cabinet card invented in England largely supplanted the carte- de-visite. Its larger format allowed the motif to be seen more clearly.

With these standardised photo cards, photography rapidly moved towards becoming a mass product in terms of forms, quality and price. After 1900, however, photo cards saw their popularity wane. Due to better papers and improved photographic and developing techniques, by the end of the First World War they had largely disappeared from the market.

Moments in the history of photography

2

Collecting

and trading

Collecting

and trading

The new, affordable formats largely forced out of the market older types of portrait photography that could only be produced as a one-off print. With the rise of the small picture cards, the uses for which photographs were intended also changed.

The collecting craze erupts: Collecting and trading portrait cards becomes social practice.

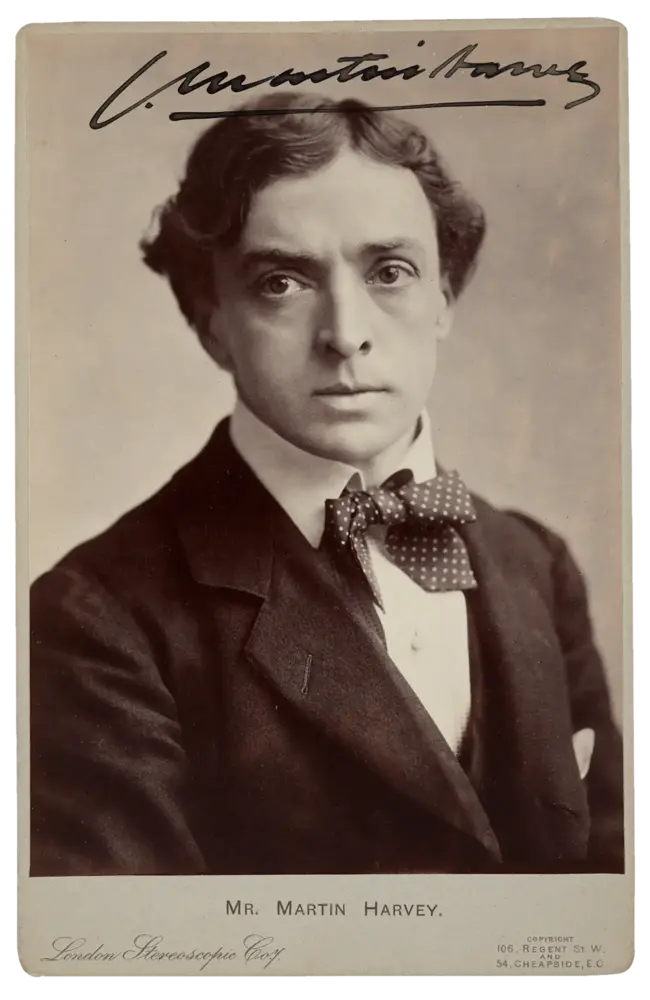

Portraits of famous personalities were particularly popular. They made up the majority of photo cards and were treasured objects of collection and trade. These pictures were produced and sold by the thousands. Their artistic standard was generally somewhat modest.

At little expense, anyone could build up a collection, e.g. with portraits of aristocrats, politicians or artists. The cards were sold in photography studios as well as in bookshops and stationers.

Fun Fact

It was easy to earn money with photographs of celebrities and consequently unauthorised duplicates soon found their way into circulation. In the middle of the 19th century, copyright did not yet exist. Only with the proliferation of these “pirate copies” did people give thought to the protection of image rights. In 1862 Britain passed the Fine Arts Copyright Law, which regulated the protection of intellectual property.

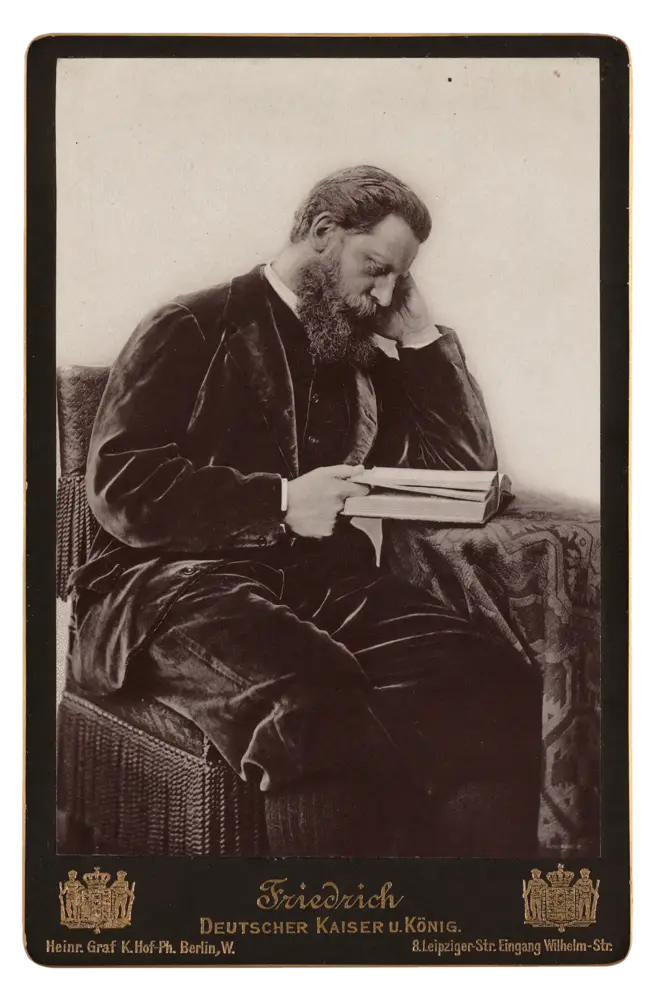

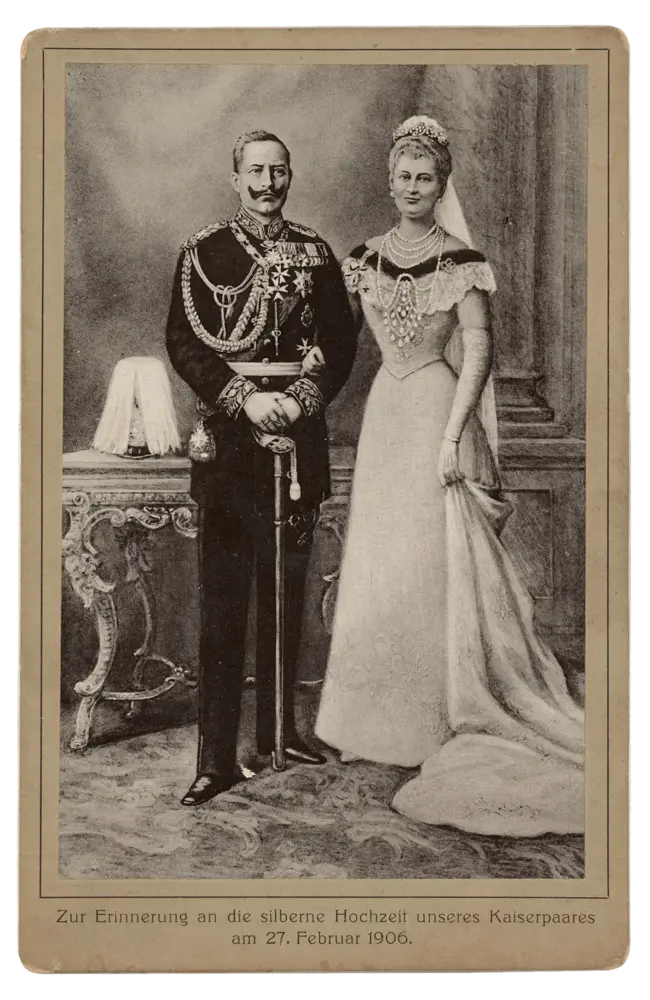

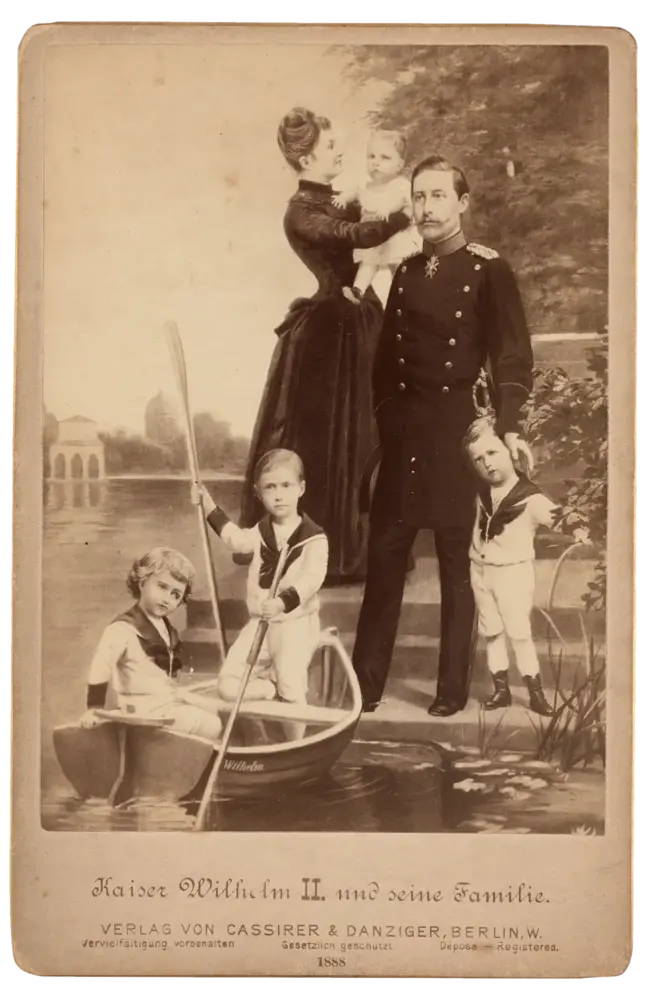

Representatives of the ruling classes and political life exploited the popularity of photo cards and used them to enhance their own image. Among the portraits of statesmen, for example, we can recognize two different types of pose:

The first is a version of the formal, official portrait, in which statesmen present a sober, dignified appearance.

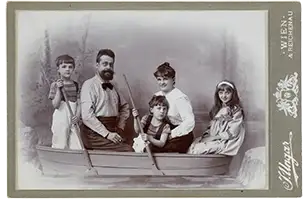

The second is a seemingly private portrait, in which the subject usually appears surrounded by family members or children. Such images were intended to increase the sitter’s popularity. Kaiser Wilhelm II was known for his skill at stage-managing his image for the camera.

Posing for one’s own portrait was not the only expression of political power. Collecting the portraits of other members of the nobility or famous individuals was also part of the culture of image-fashioning: such collections namely provided information about their owner’s social networks or were considered evidence of their thirst for knowledge. This culture also extended to the bourgeoisie.

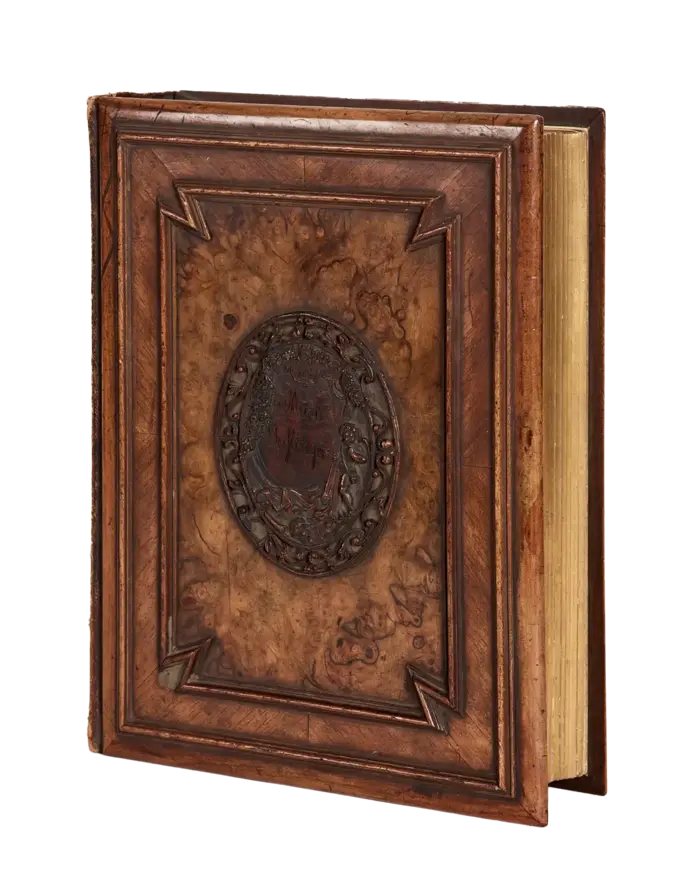

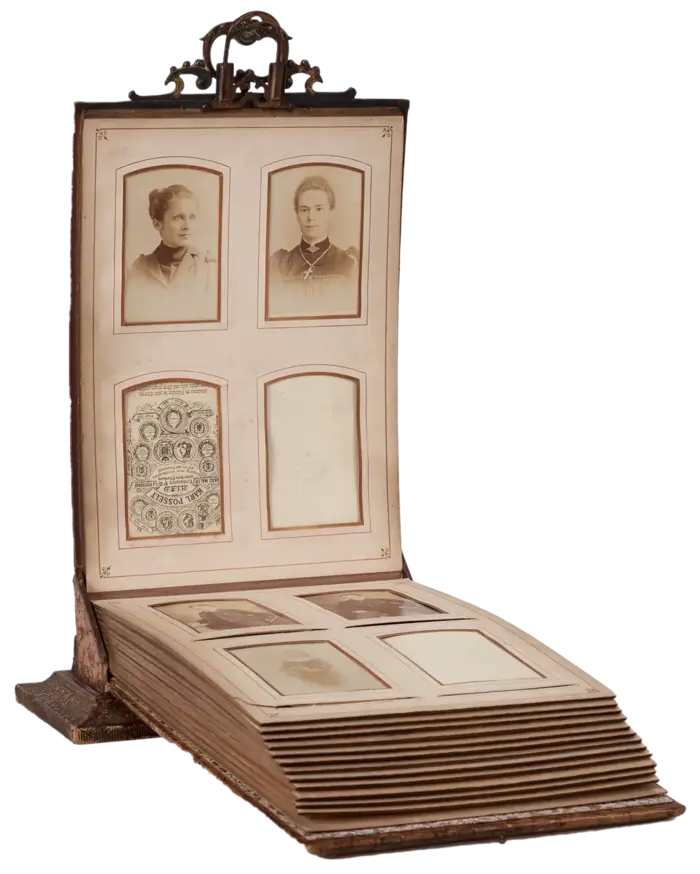

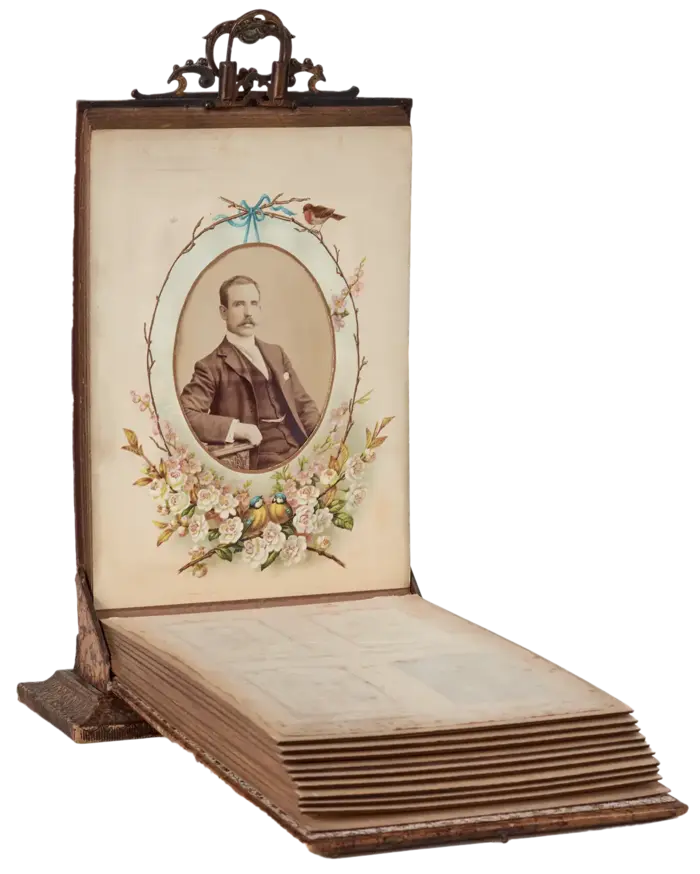

The photo album

Photo cards were initially collected, organised and stored in frames and boxes. Around 1860, the popularity of the standard-size cards led to the appearance of the first photo albums.

Photo albums were often lavishly designed. Their covers were made of leather, velvet or wood. Their clasps were ornately furnished with filigree brass fittings.

The photo album was an integral feature of upper as well as middle-class homes. Photographs of friends, relatives and even admired celebrities were kept in it and proudly shown to visitors. Such albums were considered proof of their owner’s social connections.

Fun Fact

The first photo albums were designed in such a way that the photographs did not need pasting into place. Depending on their format (carte-de-visite or cabinet card), they could be slid through narrow slits into pre-cut windows in the corresponding size. They could thus be removed again at any time.

Many a collector, too, painstakingly compiled entire albums devoted to one idol...

Marie Charlotte Cäcilie Geistinger was an Austrian actress and opera singer, celebrated by the audience as "The Queen of Operetta".

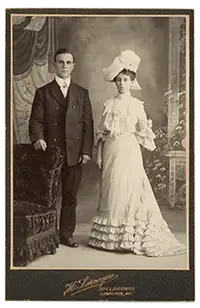

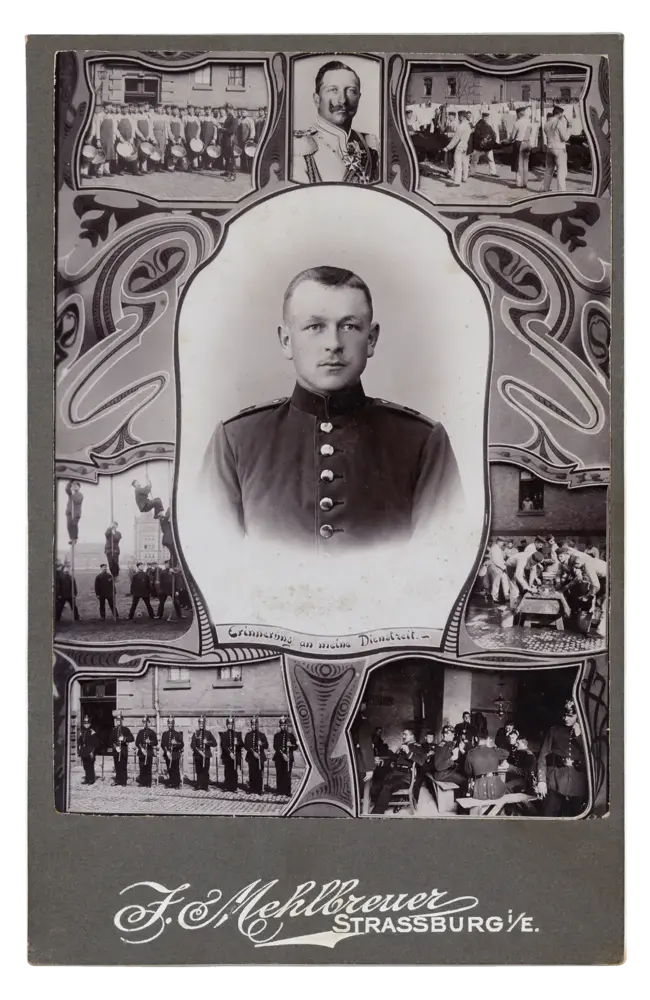

“As a souvenir of” — Private messages

Cabinet cards were not only collected and traded. They also served as a means of private communication. Now and again they carry hand-written notes and messages on the front or back.

“As a bride in my first ball gown”

“May the picture always remind you with pleasure of your grateful Ella, Vienna 16.8.1903”

“For Mr. [name] as a friendly souvenir of the pleasant stay in Marcinkowice, Rotterdam 12 Dec. 1897”

“In memory of the delightful days in Portorose, 15 July – 23 August 1897, and of the even more delightful ones in Graz, 18 October – 1 November 1897, [name] 16. XI. 1897”

“From a time without you. Your Luise, 1920”

“Happy Christmas and warm wishes from your faithful old Lotte, 21. 12. 1906”

“As a souvenir of the tour 28/7 – 12/8 1904, your grateful Theodor Wolle”

Fun Fact

The photographic image, in its function of visual record, was closely linked right from the start with recollections and memories. As early as the mid-19th century, it was possible to have your photograph taken at tourist sites and have personalised postcards printed as souvenirs.

3

Pictures make

the man

Pictures make

the man

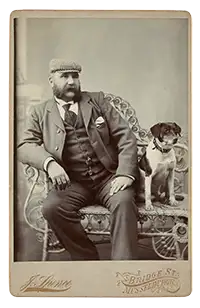

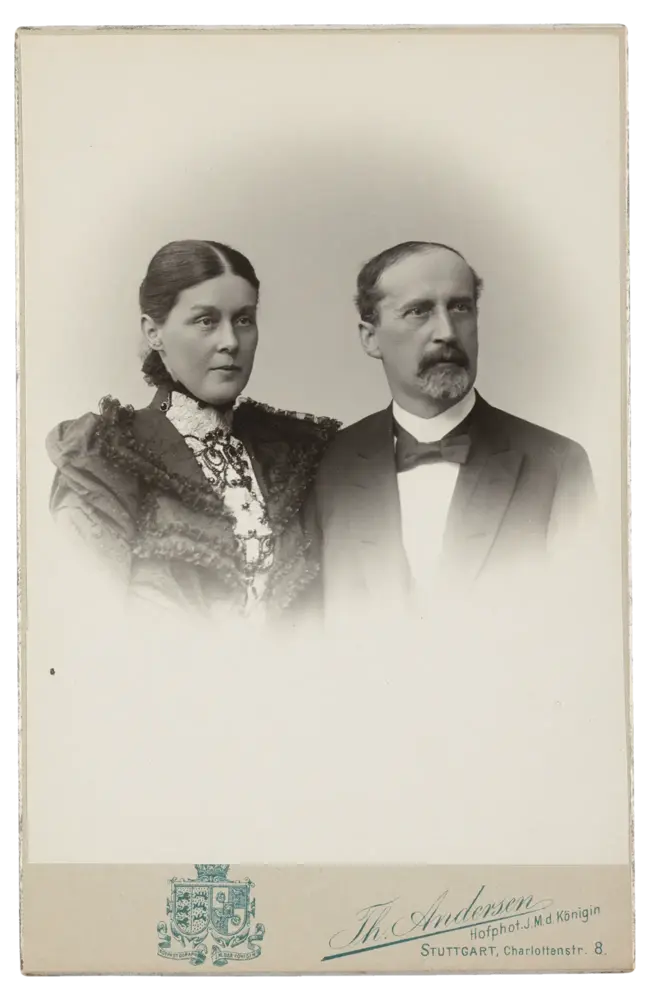

With the industrial revolution in the 19th century, a new social class emerged: the bourgeoisie. The striving for recognition and prestige led to the desire to capture one’s own individual existence in pictures. As a fast and inexpensive process, photography appeared at just the right time.

The small, inexpensive photo cards were a staple product of photograph studios and contributed to photography’s gradual spread.

The handy photo cards were much cheaper than painted portraits or daguerreotypes . This also placed them within reach of a wider clientele. An ever broader stratum of society found in photography a means of fashioning its image.

From the 1860s to the 1880s, much of the population could not afford a visit to a photographer. In these early decades, only the upper and lower middle classes benefited from the new privileges – the working classes were still excluded.

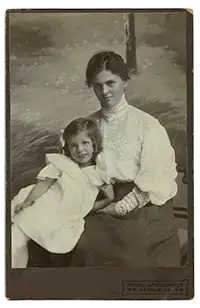

The photographic portrait developed from a means by which the aristocratic ruling classes fashioned their image to a medium embraced by the middle classes. It fulfilled the wish among members of the rising bourgeoisie for their own portraits and for seeing themselves in photographs. Having one’s portrait taken became a middle-class ritual and an everyday phenomenon.

Standardisation of photographic practice

With no other models upon which to draw, in posing these pictures the photographers fell back on forms of representation used by and for the nobility. These had developed out of the age-old tradition of portrait painting. By employing the same images, a symbolic equality was established between the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie.

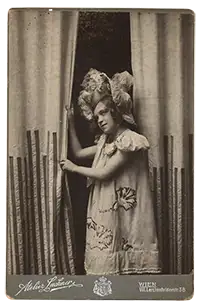

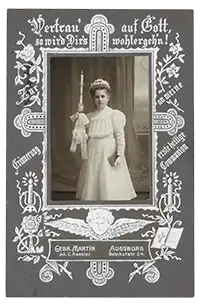

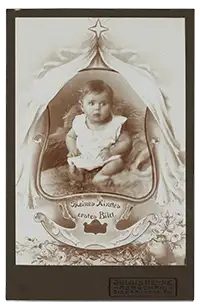

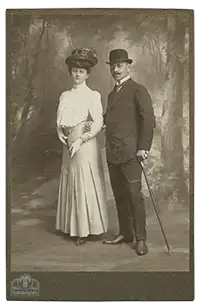

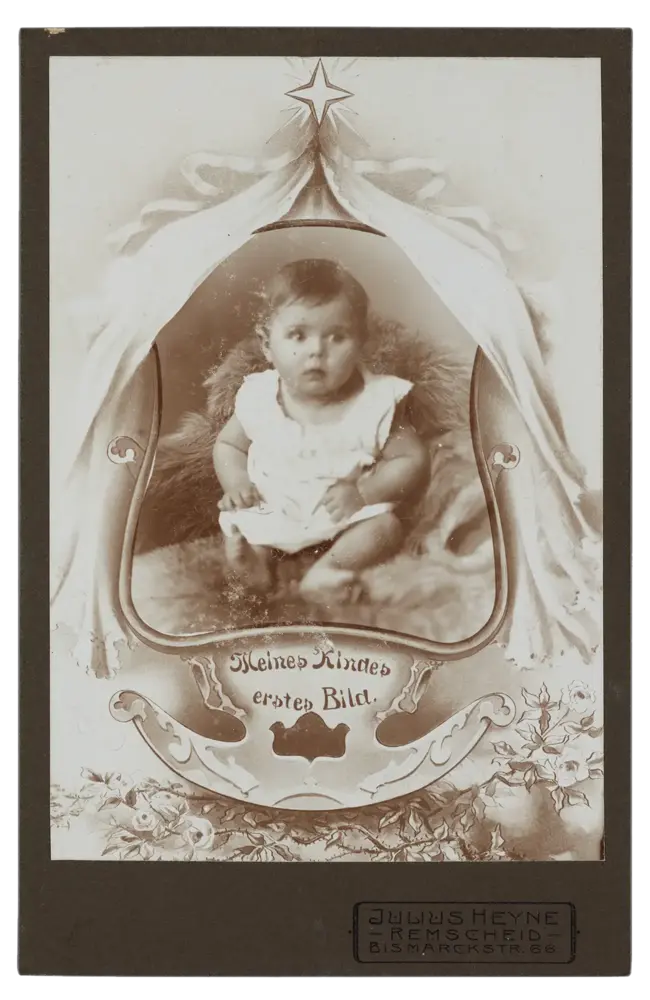

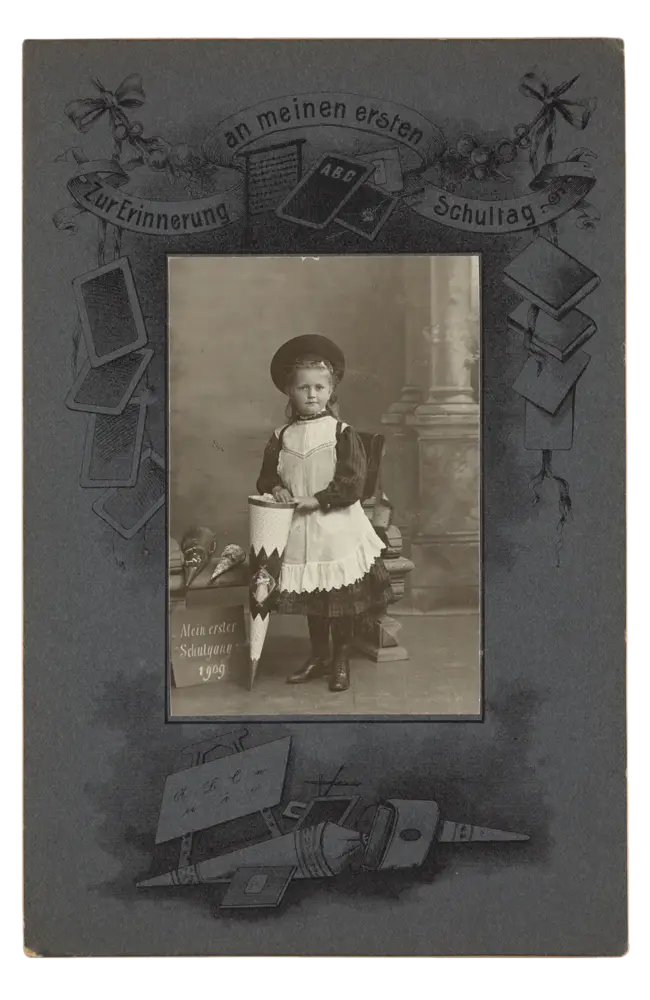

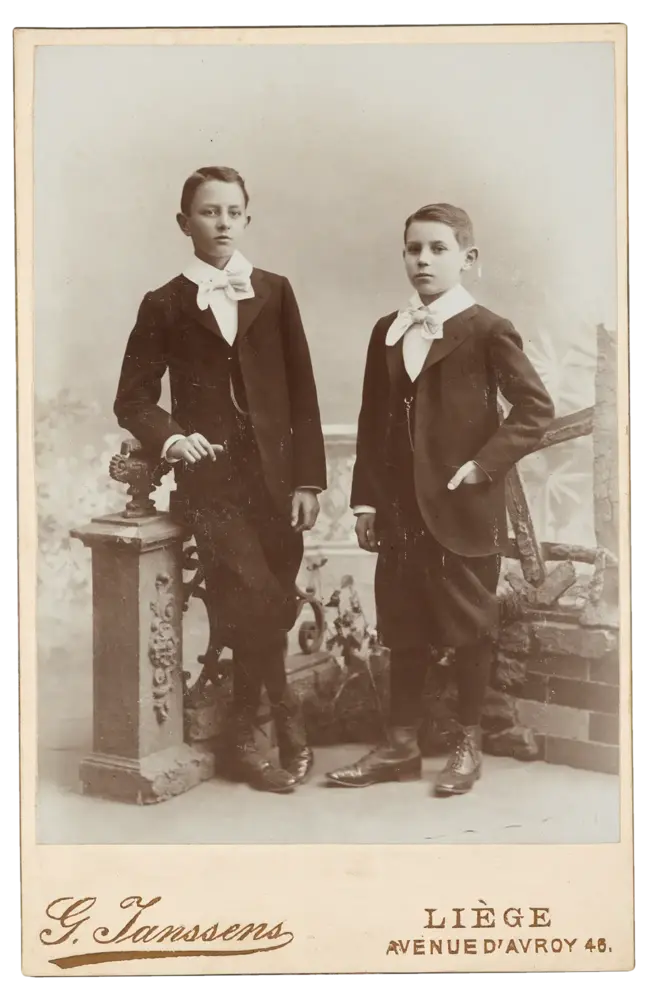

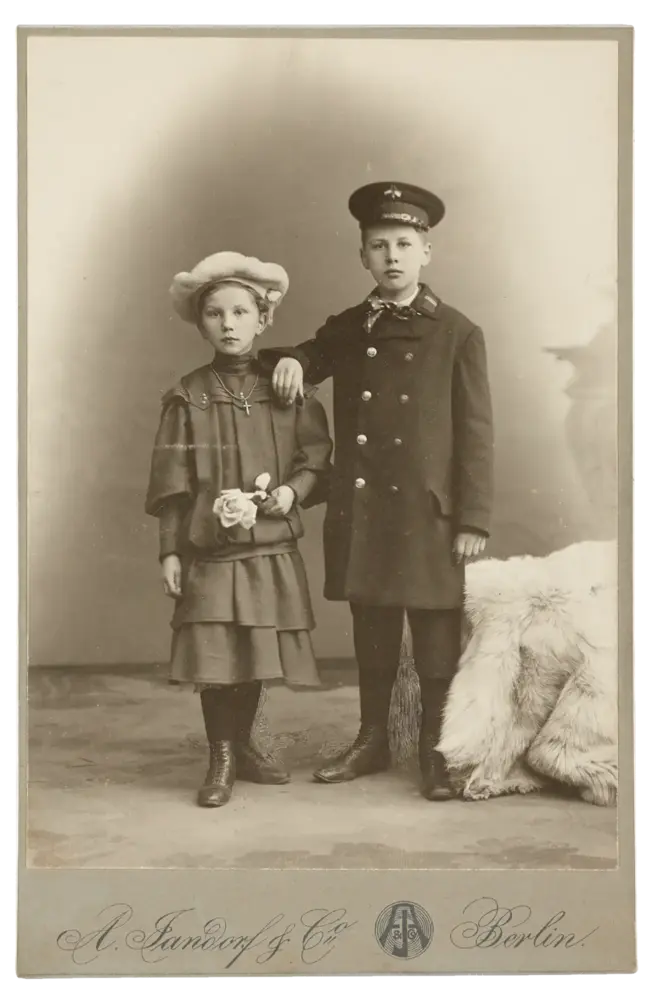

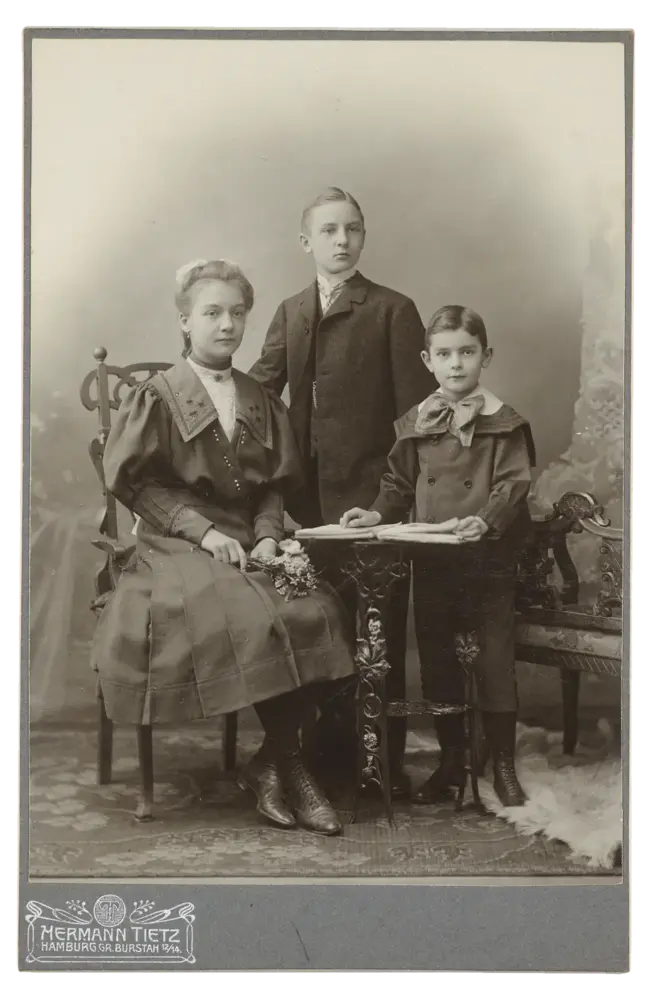

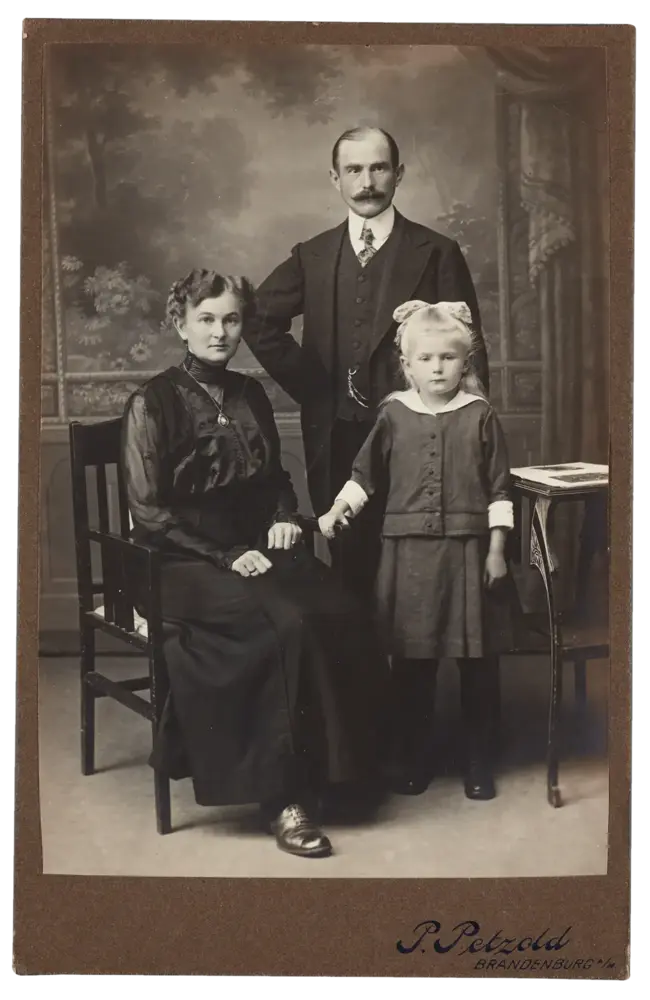

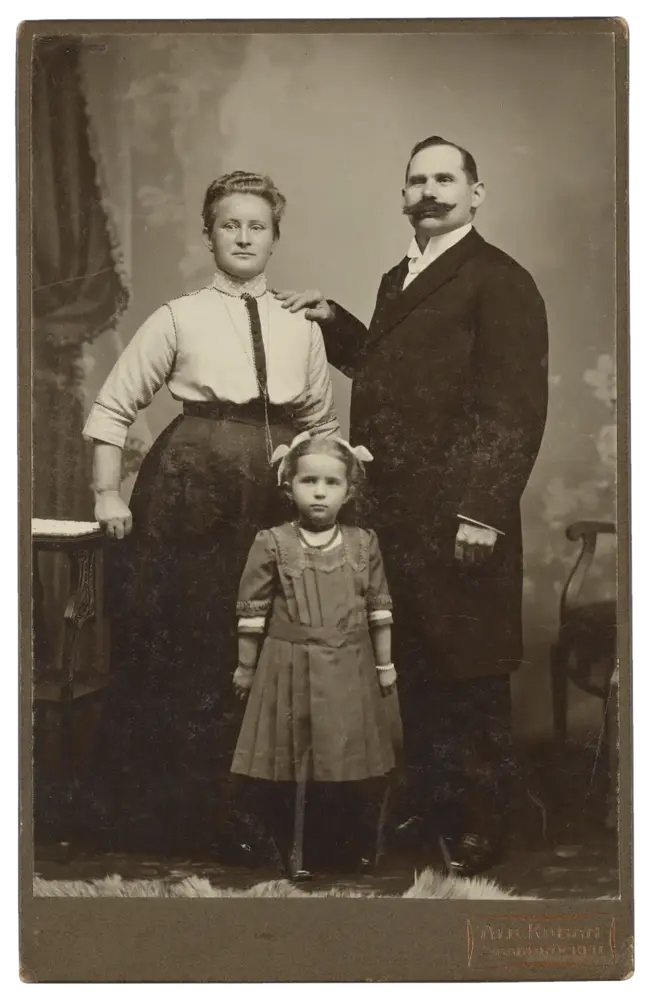

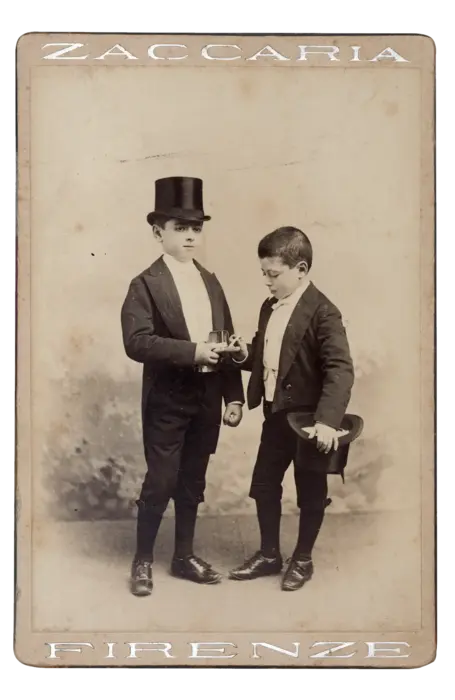

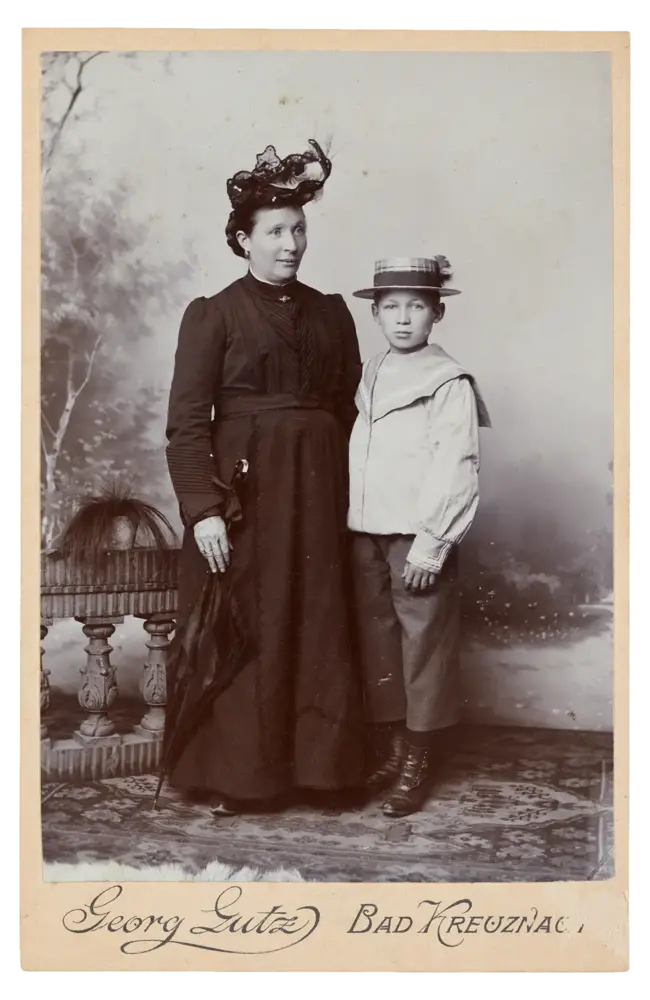

The way in which portraits are staged in part reflects contemporary middle-class thinking. Life was thus divided into different phases, which were linked with social or family events and ceremonies. Then as now, important milestones were recorded in portraits. On the occasion of baptisms, school enrolments, first communions or confirmations, marriages or wedding anniversaries, customers went to the photographer’s studio to capture these moments in a picture.

Standardisation influenced not only the format of photographs, but also their means of production and their aesthetic. What had begun as an essentially manual craft gradually turned into an industrialised process. Glass plates, papers and accessories were now made in factories. A specialist trade developed for studio equipment, too. Photography for the first time became an industrial and mass product.

With the standardised production of photo cards by the thousands, the photographic portrait suffered a loss of artistic expression and individuality. Critics see this as the beginning of the decline of photography.

“Therein lies the glory of photography. It beckons with the allure of the shop window [and] puts a pitiful name beneath a pitiful face, which was produced by a cheap process – how fortunate is that! The delight of self-righteous self-love.”

Barbey d’Aurevilly, (French novelist and moralist), 1867

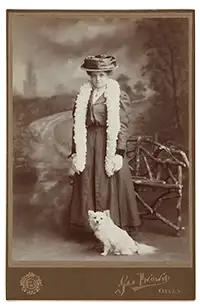

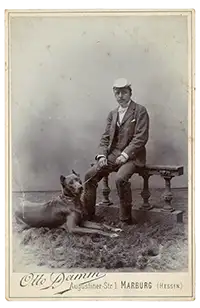

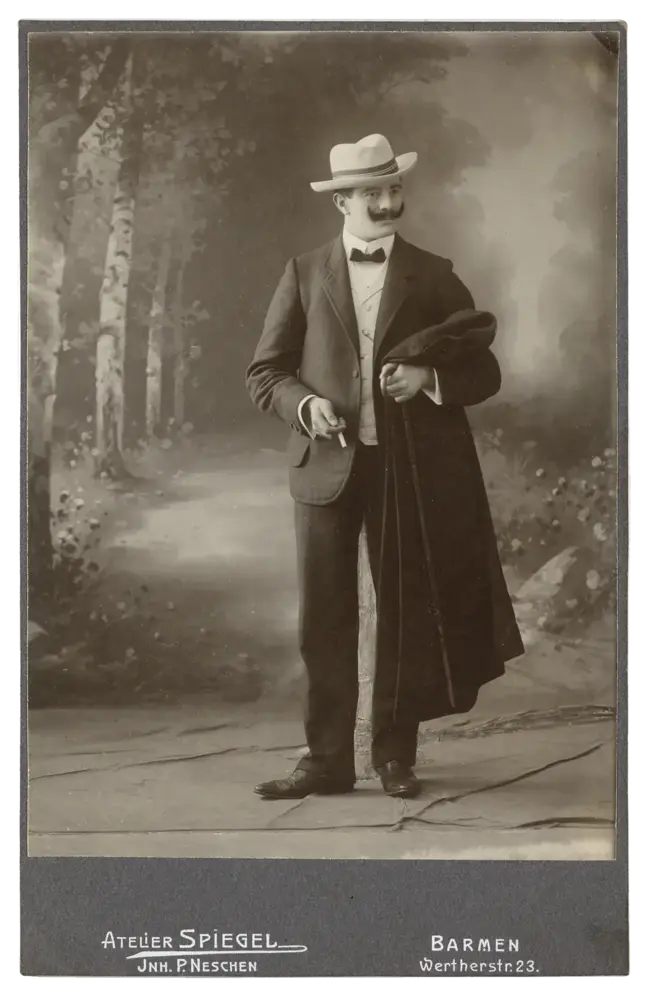

Studio photography in the 19th century developed visual formulae that were partly subject to trends in fashion. Firm rules established themselves and became the international norm. These formulae were repeated thousands of times. The result: little originality, a rule-bound composition and the same identical poses. Only a few photographers lent their work a personal touch and stood out, with their pictures, from the general monotony.

Monotony, banality, uniformity. These pictures lack originality.

The desire for individuality cherished by the middle classes ultimately led to portraits that appear devoid of character and which merely establish a bourgeois “type”. The personality of the individual sitters disappears behind a stereotypical representation.

Pages from a sample book, H. Willimec from Suderode, Provinz Sachsen, 1861/1862 © Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

Fun Fact

While they were waiting in the studio, clients could browse through so-called model books as a source of inspiration for their own pose.

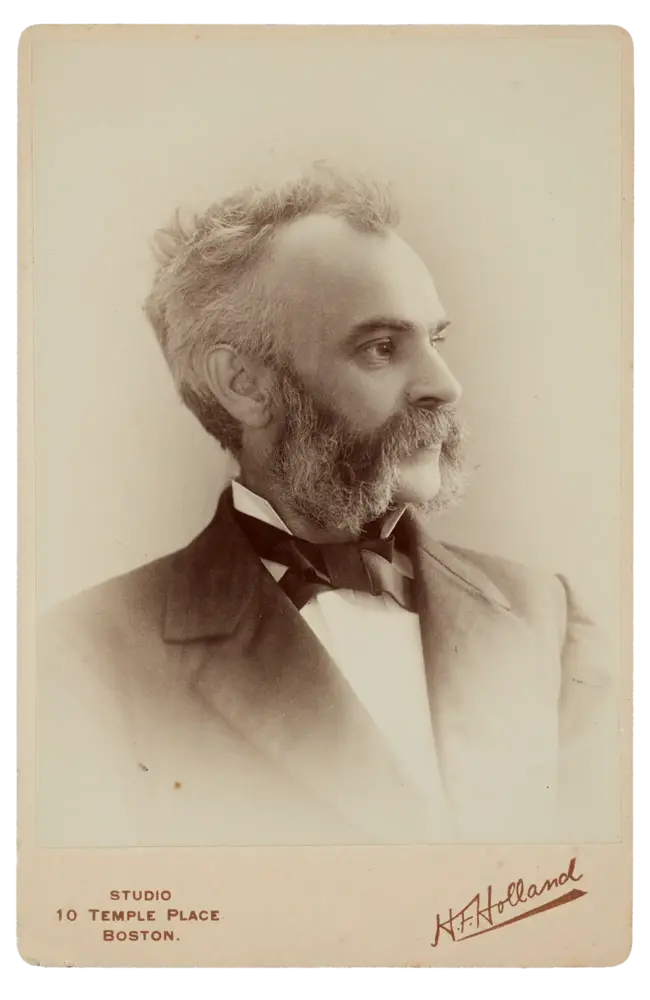

Poses and arrangements

The forms of representation used in photographic portraits followed different trends and fashions. It was at first usual to have oneself photographed either in bust-, half-, knee- or full-length against a neutral backdrop. Later, however, sitters posed in the studio amidst elaborately staged scenery.

Fun Fact

Such design trends were a means of lending the otherwise same product a fresh attraction for buyers. The aestheticized presentation changed in order to increase the cabinet card’s trade value. Innovations in product design remain a marketing strategy for countless consumer goods to this day.

One thing, however, hardly changed: poses were to be natural, upright and self-assured. The aim was to convey self-control. Expressions of emotion were to be avoided. That was social etiquette. Only in the case of young children was an exception made.

Just as today’s photographers ask us to “Say cheeeeese”, the 19th century is likewise said to have had its own catchphrase, designed to conjure the right mood for the camera…

Children’s photography

Pictures of children were particularly popular. Children were taken along to the photography studio in order to document their development and create family memories.

Only as from the age of six were children dressed in gender-specific clothing, or accompanied by attributes that indicated their future gender role. This was also how they were to be presented in their photograph.

Fun Fact

Children’s photography is considered a speciality, because it needs particular powers of persuasion to keep children still and in pose during the long exposure time. When it came to their very youngest sitters, photographers had various tricks up their sleeve …

Status is everything

The staging of photographs often reflected contemporary ideas of gender-specific roles and morality. Or it mirrored middle-class virtues. But these representations cannot always be taken at face value.

There are countless images of women reading. The book is considered a symbol of middle-class virtue. Yet very few people had access to books. Photographs were nevertheless to convey education and literacy.

In family portraits, the husband was usually staged as the head of the family. He presented himself as the dominant figure, with sovereignty over the smallest unit of society – the family. He, the husband and father, is at the top of the hierarchy and safeguards the family’s livelihood. This was to be made visible in the photograph, too.

4

The photography studio

in the 19th century

The photography studio

in the 19th century

Around 1840 the first photography studios opened in Europe and the USA. They quickly became popular social meeting places, where the experience of having one’s photograph taken, initially so unusual, soon became part of normal life.

The first photography studios were established in metropolises, always on major thoroughfares, close to the hustle and bustle of life. By the 1860s, competition in the big cities was already so great that photography studios lined the streets.

With the possibility of reproducing photographic images at a low cost, photography studios mushroomed. Whereas in 1851 there were just twelve studios in London, by 1855 there were no fewer than 50 and in 1860 some 200 commercial photographers.

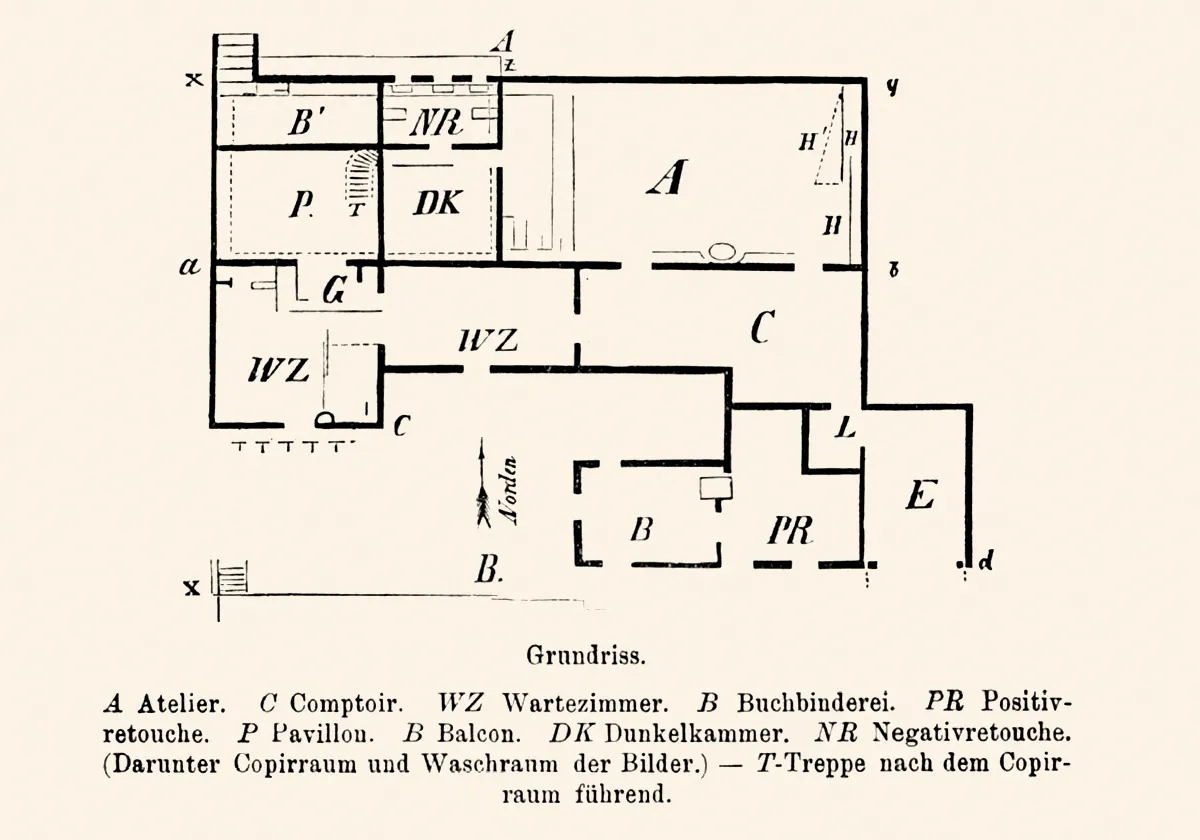

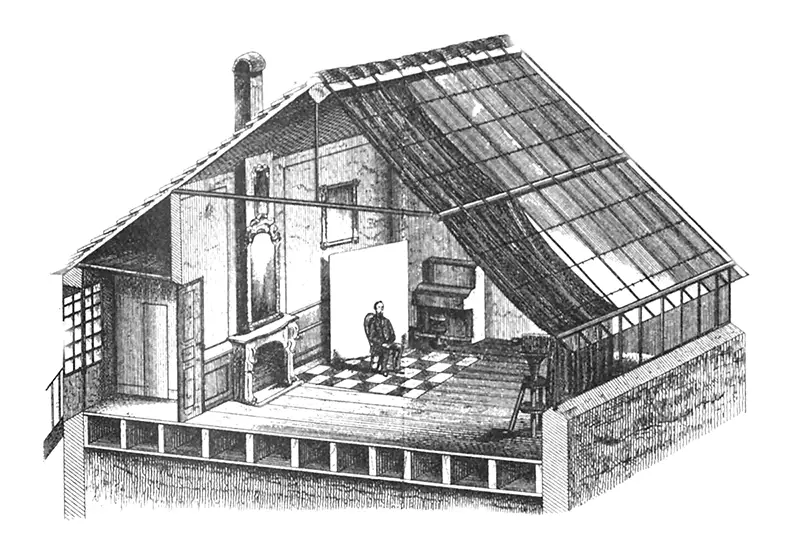

In terms of size, equipment and repertoire, photography studios ranged from small one-room ateliers to luxuriously furnished salons employing a number of staff and occupying spacious premises with a separate reception, waiting room, photography areas and laboratory.

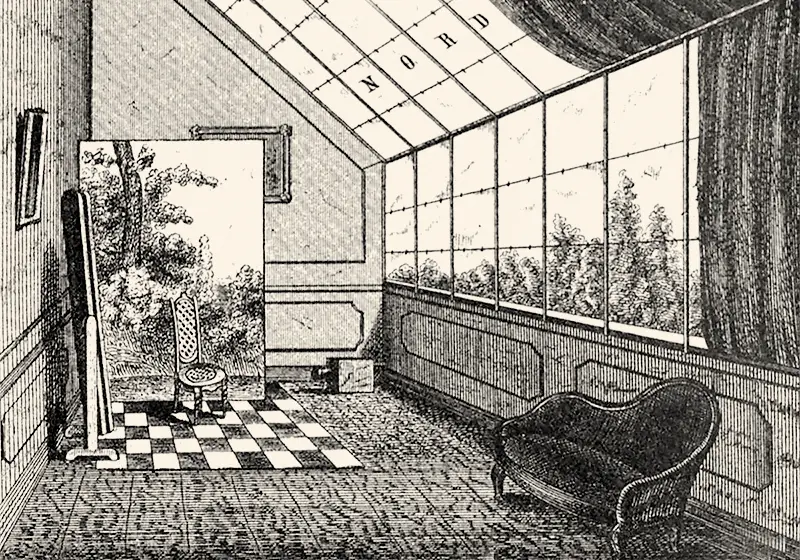

Essential to all of them, however, was a north-facing photography space with a glazed roof and glazed façade. Prior to the advent of electric light, photographers remained dependent on daylight. It was not possible to take photographs if the lighting conditions were poor.

Photographic furniture followed fashion trends. The utilitarian furnishings of the 1860s gave way, at the start of the 1870s, to serially-made photographic furniture. Proprietors used elaborately painted backdrops, papier-mâché props and draperies, as well as plants and books, to create settings for their clientele.

The most popular item of décor was a small table, on which clients could lean and so brace themselves during the exposure. This helped to avoid blurring the shot.

Fun Fact

The tables and chairs in photography studios were usually height-adjustable. This meant they could be modified to suit the height of the model.

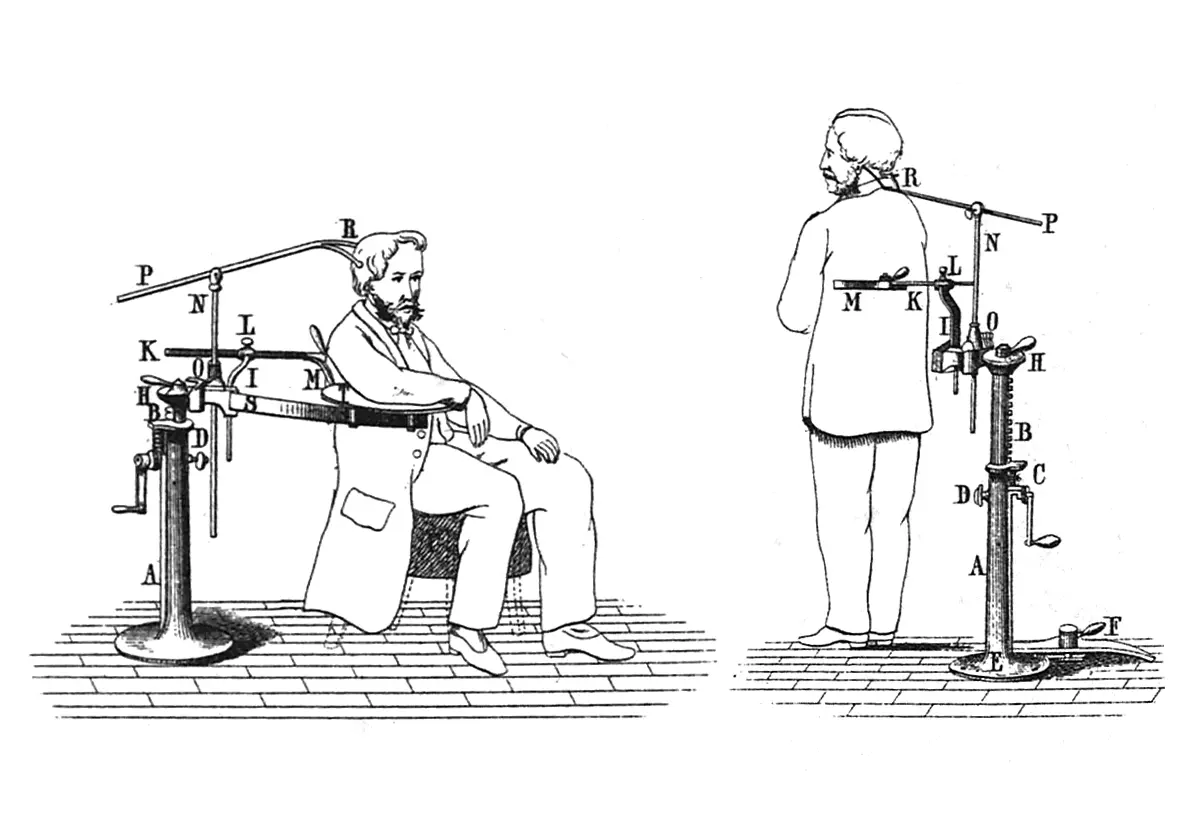

Even the slightest movement during the multi-second exposure resulted in a blurred shot. For this reason, probably every studio right up to the 20th century made use of head and body rests. These were devices that helped the sitter to keep their body and in particular their head, quite still while the photograph was being taken. In the final picture, however, such supports remain invisible.

Backgrounds were particularly important for setting the scene. After initially employing neutral, monochrome backcloths, in the 1870s photographers introduced painted variations, showing landscapes, park scenes or architectural elements. Studios often owned several different backcloths mounted on mobile stands, from which clients could choose according to taste.

Photographic furnishings served as a backdrop to the portrait but were not supposed to be recognizable as such in the final picture. Despite the photographers’ best efforts, however, it is sometimes possible to spot things that were meant to remain hidden. Take a closer look. What catches your eye?

The photographic furniture, in some cases lavish, imitated lower or upper middle-class living. It generally had little in common with the interiors in which the clientele typically lived.

In addition to a waiting room and photography area, every studio had a laboratory. Here the plates were prepared, prints made and photographs retouched or coloured.

Photography as a female profession

The photographers known to us from the early days of photography are mostly men. Nevertheless, there were also women working in photography studios in the 19th century and practising the profession of photographer. Most of them, however, remained anonymous.

As from the late 1850s, women were employed mostly in assistant roles, for example as:

-

Copyists made prints from the negative images.

-

Retouchers performed the task of retouching the photographs.

-

Operators assisted on the shooting of the picture. This could include e.g. setting up the lighting and camera, posing the sitters and preparing the plates.

-

Receptionists were responsible for customer care and sometimes also for office duties and bookkeeping. This was a profession practised exclusively by women.

It was rare for women to run their own studios. They more commonly occupied positions in studios headed by men. They did not work under their own name and consequently had no public visibility. This was also true of wives of studio proprietors who took over the business after the death of their husbands.

But there were also highly regarded women photographers with their own studios, who enjoyed national renown. Some of these women won prizes in competitions and earned the title of “Hoffotografin”, or “royal photographer”. They were in no way inferior, in other words, to their male colleagues. They included:

Anita Augspurg

Laura Bette

Emilie Bieber

Johanne Birkedahl

Julia Margret Cameron

Katharina Culie

Anna Dencken

Sophia Doudstikker

Bertha Eysolt

Charlotte Frank

Adele Köttgen

Stephanie Ludwig

Maria Mertens

Adele Perlmutter

Emma Plank

Evelin Schulz

Bertha Wehnert-Beckmann

Emilie Vogelsang

Fun Fact

When choosing a professional name, women photographers often used abbreviations or made-up names as a protection against discrimination. Katharina Culie, for example, usually worked under the name K. Culie, while Stephanie Ludwig called her photography studio the Atelier Veritas.

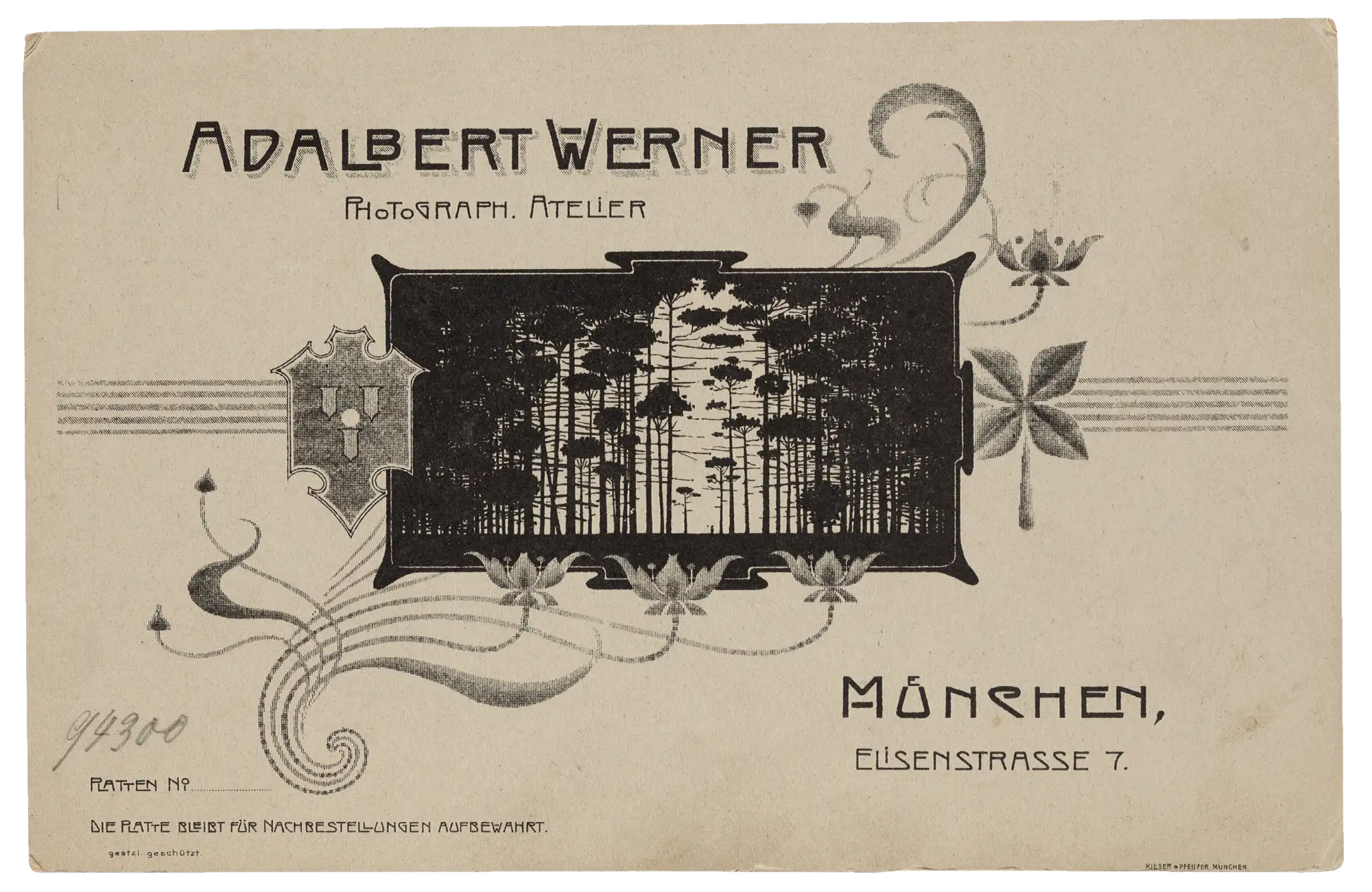

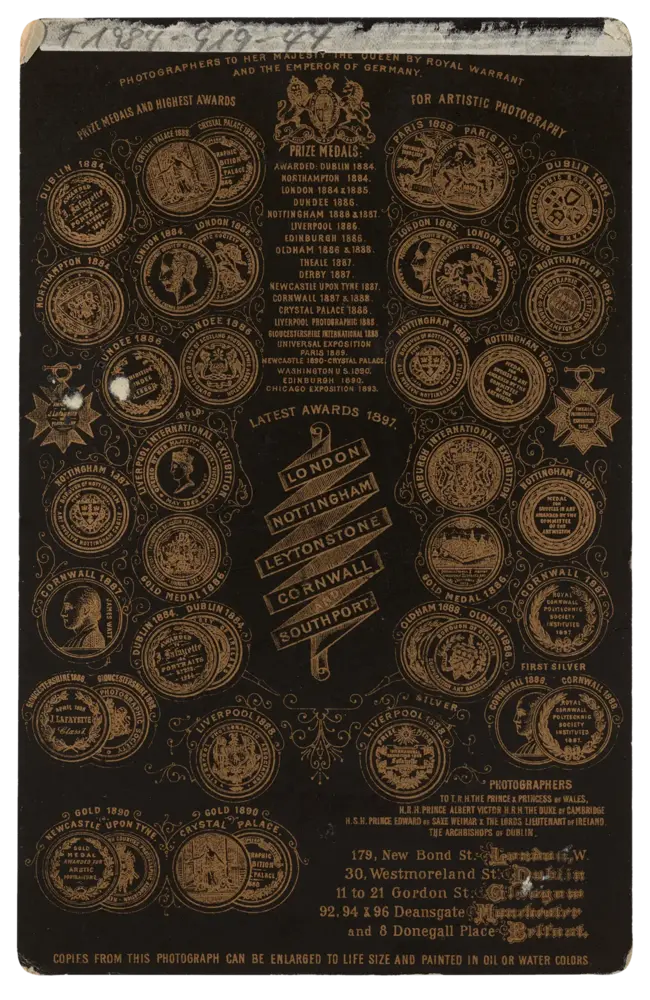

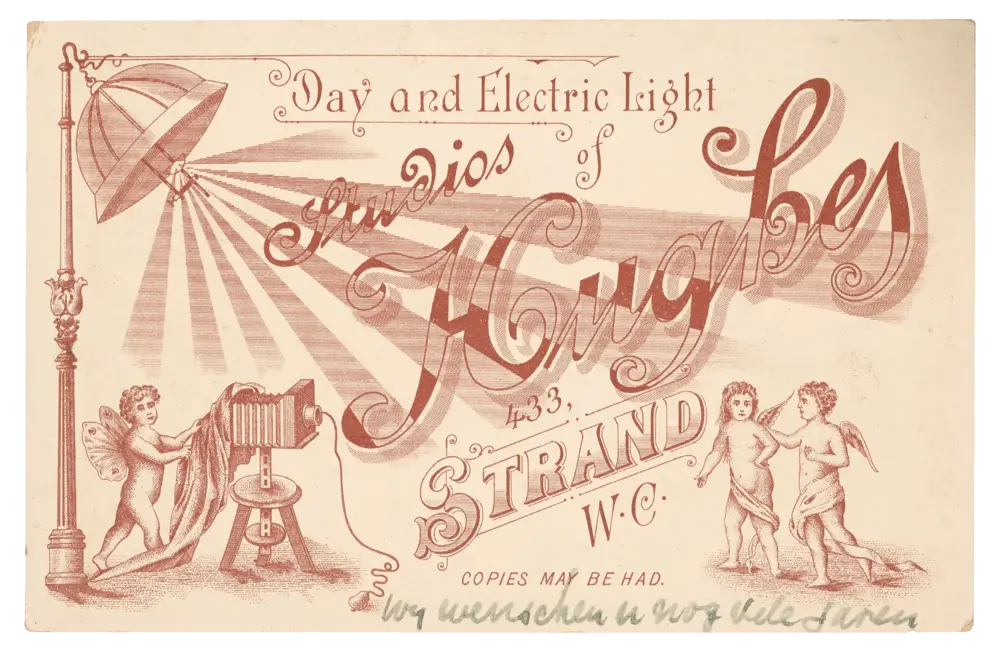

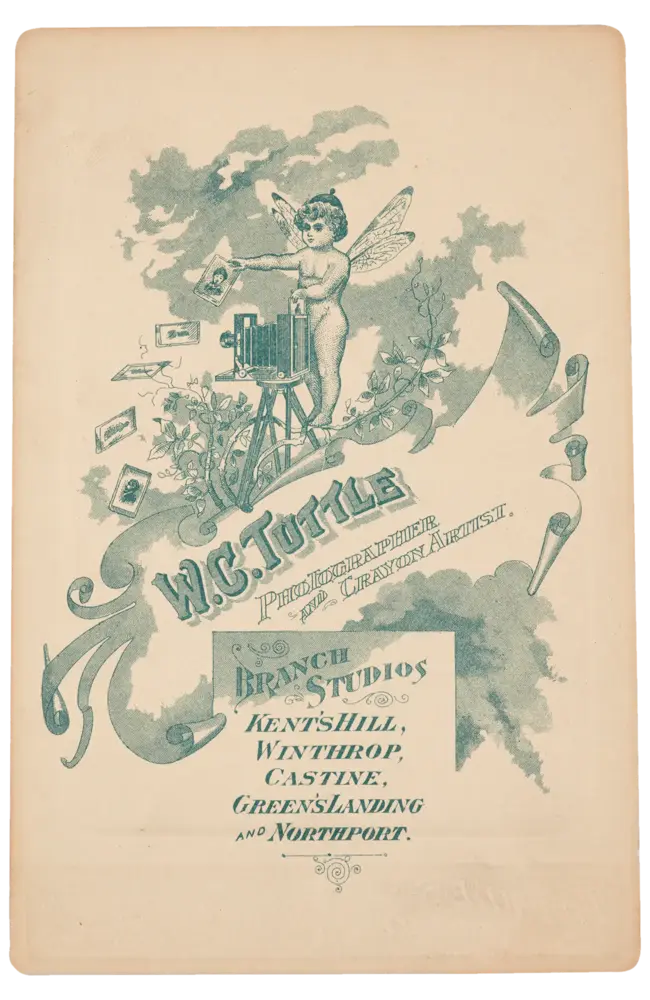

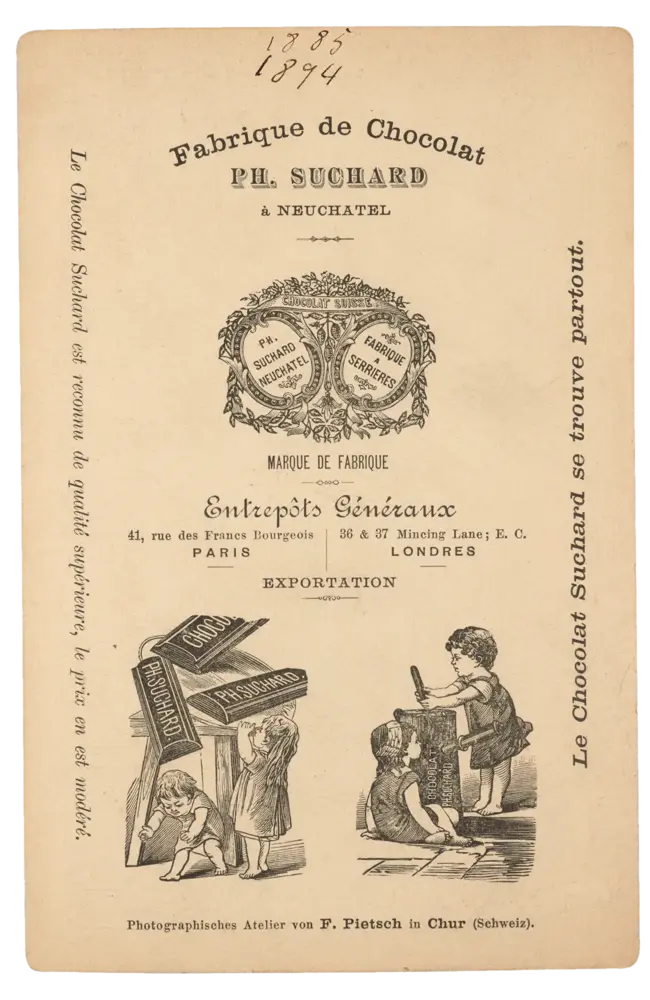

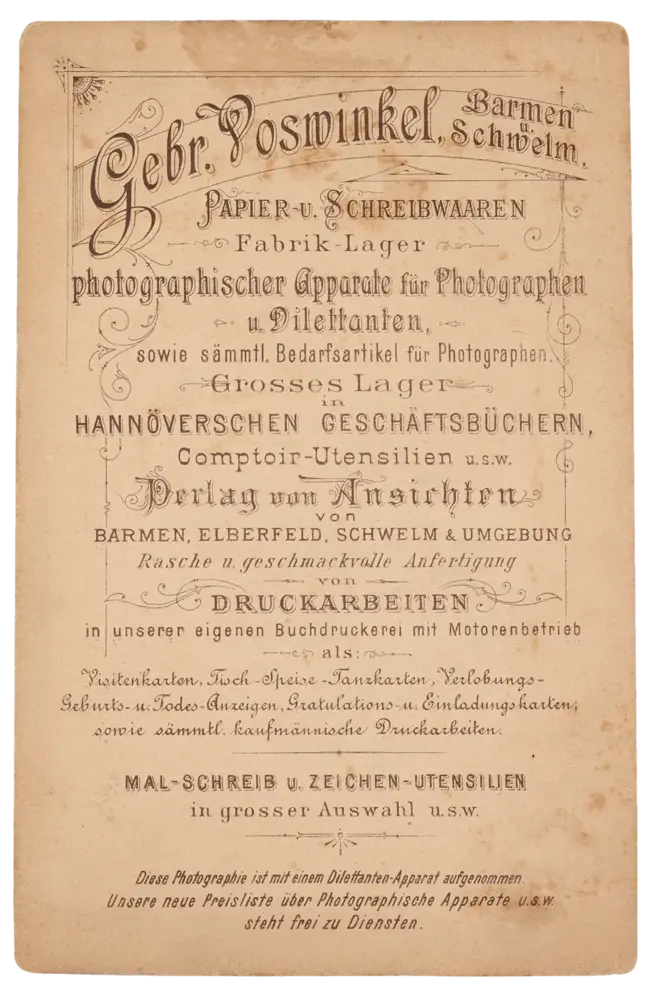

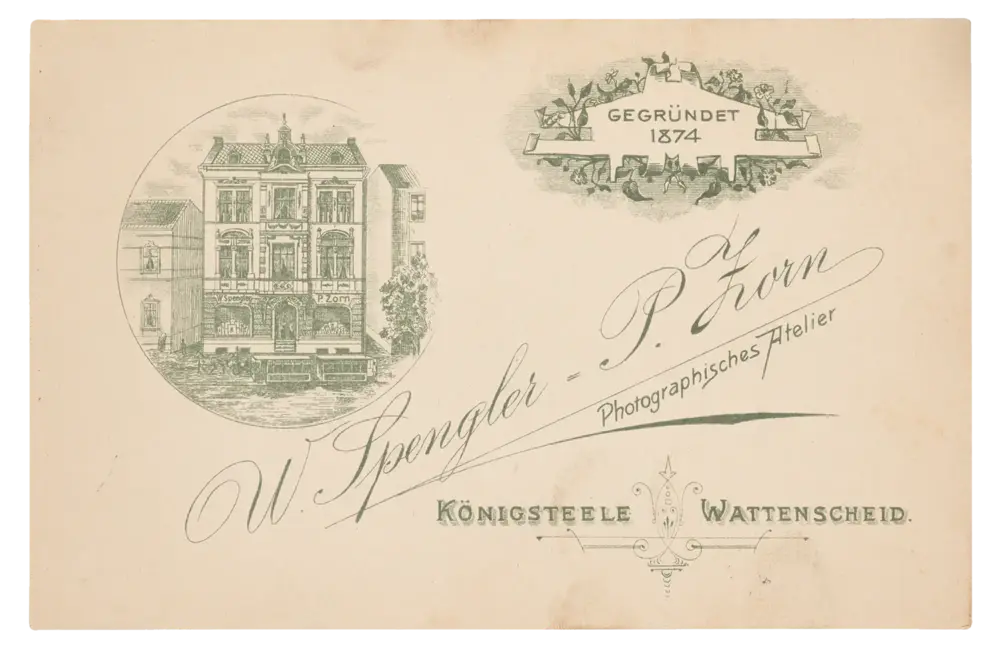

The back of the card as marketing strategy

Given the huge competition, it was important for photographers to attach their names to their work. This was initially done by printing their name and address on the front of the photo card. Gradually, they also began to use the backs of cards as an advertising medium.

Alongside information about the studio, proprietors cited honours and awards or included a list of other branches, in order to underline their achievements and activities.

The back was used as a marketing space, with information about opening hours, prices and specialist services such as child photography.

These details were accompanied by artistically designed illustrations, for example showing painting implements or muses and putti engaged in making art. These illustrations served as an expression of the photographers’ understanding of themselves as artists.

Fun Fact

On some cards we can read “nur bei gutem Wetter” – “only in good weather”. Since electric light had not yet been invented or was not yet accessible to all, it was only possible to take photographs when natural lighting conditions were good. Many a portrait sitting was thwarted by a cloudy sky. For photographers, this dependency on the weather only vanished with the gradual spread of electric light.